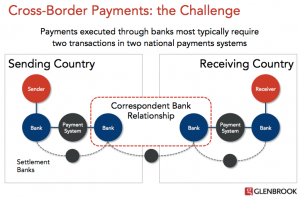

As globalization increases, businesses of all sizes buy goods and services from overseas suppliers and turn to new customers in overseas markets to drive growth. As a result, the demand for cross-border transactions steadily increases. The vast majority of these transactions takes place through correspondent banking relationships and collectively described as “international wires.” The reality is that there is no such thing as an international wire. Each country has its own payment systems (with the exception of the EU, but let’s think of them as a country, for these purposes). There are typically two flavors of bank transfers: option one: an ACH or credit transfer system, generally slower and cheaper; and option two: wires, which are faster, typically irrevocable, and more expensive. These payment systems only work within their respective countries. Typically only banks that are licensed and regulated in a country have access to its payment system. Payment system transactions are denominated in the currency of their respective country. International transactions rely on cooperation between banks in different countries that access the domestic system on either end of the transaction. This cooperation is formalized through a series of bi-lateral correspondent banking relationships. Often smaller banks rely on larger banks in their country to conduct cross-border transactions. The diagram below illustrates how banks rely on one another:

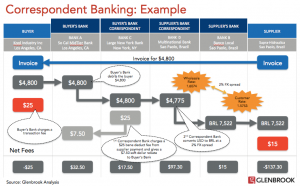

International correspondent banking is, in essence, a giant, decentralized network. Each bank makes a decision as to how it wants to handle cross-border payments for its customers. These decisions can be—and often are—different for paying and receiving funds, and for different countries/currencies, or categories of payments (e.g., B2B payments vs. person-to-person remittances). Let’s look at a more detailed example (refer to diagram below)

Step 1. A supplier ‘Supra-Hidraulica’ sends its customer ‘Kool Industry’ an invoice for $4,800 and the details of its bank account at Banco Local in Sao Paulo, Brazil (Bank B).

Step 2. Kool Industry banks with ‘So Cal Midtier Bank’ in Los Angeles (Bank A). In order to send $4,800 USD to its supplier in Brazil, someone from Kool Industry’s finance department either goes to one of Bank A’s branch locations and fills out a form or enters payment details in the Bank A’s business version of online banking.

Step 3. So Cal Midtier Bank has chosen a domestic correspondent in New York, Bank C, to handle its payments; it makes a payment to the New York Bank through its US wire transfer system. At this point, the So Cal Midtier Bank is finished!

Step 4. The bank in New York has an arrangement with a fourth bank, Bank D which is a Multinational Bank in Brazil to handle such transactions. Bank C in New York notifies Bank D that it wants a domestic Brazilian wire transfer sent from Bank D to Bank B, to credit Bank B’s customer, Supra-Hidraulica.

Step 5. Bank D effects the transaction and Bank B receives funds—which it credits to its customer’s account.

All pretty straightforward—but one piece is still missing. Bank C in New York has the money and Mulitnational Bank D in Brazil has sent it out—how are these positions settled? In this example, as a part of their correspondent banking relationship, Bank C and Bank D have agreed to settle their transactions daily, on a net basis, by making funds available/withdrawing funds from a set of accounts both banks hold with one another. But there are no rules here: it is entirely up to the business arrangement that the correspondent “pair” has negotiated. That negotiation, by the way, covers fees, balances, and who-gets-to-do-the-FX as well. At the end of the day, money doesn’t cross borders. There is no international wire, just a series of domestic transactions. One bank ends up with more money in its correspondent account: the other bank ends up with less money in its correspondent account. When considering how this works, keep in mind that each bank is making an independent decision about how to send, receive, and settle payments. The possible combinations and variations are staggering. From an economic perspective, the bank that performs the currency conversion typically earns the most on any given transaction. In our example the Multinational Bank in Brazil earned $97.30 for performing its part. The other correspondent, Bank B in New York, compensated itself by ‘lifting’ some of the value from the transaction. This practice is called “bene deduct” referring to the fact that the transaction recipient, or beneficiary, experiences a reduction in funds. The correspondent relationship negotiation between Bank A in Los Angeles and Bank B in New York specifies that Bank B share that “bene deduct” revenue, which is does. Both the Buyer and the supplier pay fees to their banks as well. There are great advantages to users of the current system of international correspondent banking. As virtually all banks participate in some manner, it is global by definition, broadly understood within the banking industry, and comprehensive in its reach. Such a decentralized, non-standardized approach has inherent problems, however—problems that can cause pain for some corporate and retail customers. Challenges include:

- No direct relationship with downstream banks. If a problem occurs (for example, a payment is not received or is delayed), the sending company—and its bank—may not be able to trace the transaction quickly or reliably.

- Cost. With multiple banks involved, each charging a fee and/or taking some share of the foreign exchange revenue, these transactions can be expensive for end users. Often, end users do not know whether costs are also assessed to their counterparties.

- Limited data transport capabilities. The payment initiator may wish to send information with a transaction; with multiple bank intermediaries involved, it may not be possible to reliably carry that data through to the receiving party.

- Barriers to change. In a decentralized system, it is relatively difficult to implement change. There is no central authority to mandate or direct new processes. Of course, we should acknowledge that SWIFT does play an important role in enabling change through setting and promoting new standards. But it cannot dictate the terms of correspondent banking relationships—so that there is no uniform way, for example, for a sending bank in one country to change the ways in which payments are made by its correspondents in receiving countries. For example, attempts to migrate more transactions to ACH from wire still demand tedious and laborious point-by-point negotiations and implementation procedures.

I am writing this post on an airplane, en route to Amsterdam for Bitcoin 2014 where I will be exploring alternatives to the complicated, unpredictable and expensive correspondent banking process. If you happen to be in Amsterdam, too, and want to talk cross-border B2B pls reach out via Twitter: @erinmccune This post was written by Glenbrook’s Erin McCune.