The interdependence of eGovernment and government ePayments is yet another classic payment chicken and egg challenge. As we work with governments to build their electronic payment strategies we sometimes need to temper their expectations given this all-too-familiar challenge. There have to be enough digitally delivered government services to warrant digital payment infrastructure, but you also need scalable, robust digital payments to support digital delivery of government services. At Glenbrook we’ve started calling this the “eGovernment-ePayment Conundrum” – and only partly in jest.

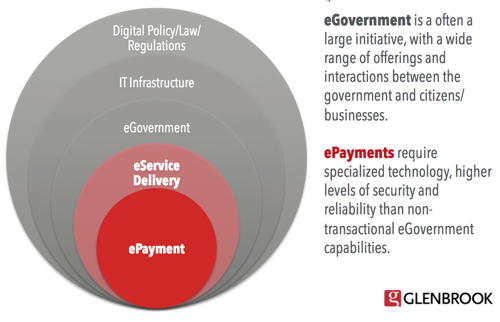

As I explored in an earlier post, ePayments are often an afterthought when it comes to eGovernment initiatives. Yet ePayments are a critical enabler of eGovernment. There are only so many non-fee services that government agencies can offer to citizens that are also compelling enough to drive momentum for eGovernment participation. So, key questions include:

- How can you build government eServices momentum while simultaneously expanding robust digital payment infrastructure to collect the associated fees?

- What factors contribute to this dilemma?

- More importantly, how do we solve it?

Policy, Law & Regulatory Challenges

At the time they are enacted, laws and regulations hopefully reflect the best-available information and policy decisions. As technology changes, however, laws can become obsolete or, worse, become barriers. For instance, if cash is legal tender, does the government have the legal right to require electronic payments and not accept cash? Are required receipts and consumer disclosures permissible for delivery using the new channels and devices? Are laws and contracts clear on the liability and responsibilities of banks, and non-banks, handling ePayments?

Recognizing the importance of modernized regulations, the UK, under a provision titled “Action 12,” has required all national ministries and independent agencies to publically commit to revising pre-existing laws that impede the country’s “Digital by Default” initiative.

Technology Challenges in Developing Markets

In developing markets, government agencies may not have digitized records and sophisticated billing systems. ePayment ambitions may need to wait until ministries, departments, and agencies are sufficiently digital to gain critical mass. A productive possibility is to pilot ePayment approaches with a small number of enthusiastic government entities.

Similarly, citizens and businesses may remain stubbornly reliant on cash and manual processes. Efforts to digitize government must match the general pace of internet and communications infrastructure growth, computer knowledge, and access to digital financial services (more on financial inclusion and the key role government payment in an upcoming post).

Technology Challenges in Developed Markets

In developed markets, government agencies have another sort of technological challenge. They may be hampered by outdated legacy internal systems that are inflexible and difficult (read “expensive”) to connect to modern web interfaces. Some governments suffer from outdated Internet infrastructure. How many of us have visited a relatively old government or municipal website and paused before entering our payment information thinking “what year was this website developed? Is it even safe to enter my credit card number?”

Organizational Challenges

eGovernment organization, steering, and oversight structures typically align with program goals. For example, programs in countries that view eGovernment as a major technological initiative tend to report into information and communication technology (ICT) agencies, whereas programs with economic development missions generally report to the Executive or special purpose agencies.

The implementation of eGovernment services is an enormous undertaking, given the wide range of government entities with varying degrees of technological infrastructure, different (and possibly contradictory) policy ambitions, and to put it delicately, different levels of political influence. It is no wonder these initiatives last many years – even decades – and success is dependent on leadership’s organizational change skills as much as technological savvy.

Knowledge and Skill Challenges

To build and maintain citizen trust, payments require specialized knowledge, have specific data security needs, and must be processed quickly and reliably. No government official wants to be responsible for loss of taxpayer funds, or for compromising citizen payment credentials. For these reasons, the Central Bank or Department of Treasury is often charged with delivering ePayment regardless of where the overarching eGovernment program resides.

Examples of ePayment-eGovernment Production Systems

What can be done to overcome the ePayment-eGovernment Conundrum? Consider three examples where government entities share payment infrastructure:

- The government of Singapore came up with an enterprise architecture that links business functions, relevant data standards, common systems and services, and technologies. The architecture works across agencies in order to achieve integrated, government-wide goals. As each agency contemplates new eGovernment capabilities, it can draw upon a database of reusable services, each described in a standardized way, each “owned” by the agency that developed it.

- Fatourati in Morocco is an example of a multichannel bill-payment system, used by government entities as well as other billers. It is owned by eCommerce merchant aggregator Maroc Telecommerce, itself a subsidiary of card network operator CMI (Centre Monetique Interbancaire), founded by 9 Moroccan banks. The solution uses the proprietary “Transact” e-commerce product from Chicago-based Souverain Software and cash transactions are handled by third-party Wafacash network of 1000 cash in/cash out agents.

- In the United States, government payments are often provided by a vendor specializing in bill payment. Individual government agencies work with the vendor of their choice. These solutions are increasingly multi-channel, supporting a range of payment methods—online at a bank website, at the government agency website, in person, or by phone.

Alternatively, some U.S. government entities elect to utilize the gov service offered by the Department of the Treasury. Over time, this service has created multiple processes that are used by hundreds of agencies to integrate with a centralized payment infrastructure. They include:

- Basic forms service – The Pay.gov entity electronifies simple online forms for individual agencies and facilitates payment collection

- Collections control panel – a virtual terminal that allows agency personnel to take payment over the phone, or in person

- E-Billing interface – an agency sends a data file to Pay.gov, which in turns sends an electronic bill to a consumer via email, with a link to pay

- Trusted Collections Service – facilitates large volume card and ACH transactions for higher volume agencies such as Customs and Border Protection. Card transactions can be real time or batch via ACH

- Open Collections – a legacy interface for bulk collections that is gradually being phased out in favor of #4

- Agency Adaptor – supports batch transactions for ACH. This is used for very high volume services such as student loan payments.

Glenbrook advises its clients to pursue a centralized payment infrastructure model, operated by the Treasury or Central Bank on behalf of various government entities. This approach most effectively supports a broader government transition toward modern eGovernment.

In the coming weeks, we will continue sharing lessons learned in building ePayment capacity. If you have a government success story to share, we want to hear it.

This post was written by Glenbrook’s Erin McCune.