By Elizabeth McQuerry, Cici Northup, & Victor Malu

Introduction

Glenbrook is based in the U.S., but we work on projects around the world; our global practice often supports clients in emerging markets. From time to time, for more formal proposal processes, we are asked to provide a corresponding bid security. For anyone not familiar – a bid security can help to ensure legitimacy of proposing entities. It’s a formal process that typically requires a banking entity to carry out the process by holding funds in a sort of escrow. It helps ensure that the proposing entity holds itself accountable to the presented bid. This post attempts to capture this process and also illustrates the challenges and uncertainties that sometimes are part of the cross-border payment process. We encountered uncertain timing, high fees, and low transparency in terms of both cost and process as we moved money from the U.S. to an entity in Rwanda.

Getting the bid security to Rwanda

We were unable to directly manage a bid security in Rwanda. Long story short – our bank (a top five financial institution in the U.S.) could not provide this service for projects outside of the country, and the half dozen international surety bond providers we contacted could not do it given the bond size (saying it was too small) or licensing constraints (e.g., not having license in Rwanda). Fortunately for us, we were collaborating with Victor Malu, a colleague in Kenya, who was able to make this happen on our collective behalf. (For those of you who don’t know Victor, he is a finance expert based in Nairobi). We couldn’t have done this without his collaboration and human intervention.

Here are the steps (and the nitty gritty details) it took to send and ultimately repatriate the funds.

First step: funding an account in Kenya

Glenbrook sent $3,000 U.S. dollars (USD) to Victor’s account in Kenya via a wire transfer. Knowing that the cross-border payment process comes with unknowns (e.g., the payment could lose value along the way through a beneficiary deduction, or the foreign exchange rate applied could swing) we sent additional funds so as to have a buffer if needed.

Second step: funding the bid security in Rwanda

Having already confirmed that the large commercial bank where he had his account could handle these arrangements (i.e., get the bid security), Victor requested his bank to fund the 3,000,000 Rwandan francs (RWF) for the bid security (once he received our wire transfer). This step is notable because no money was transferred to Rwanda. Instead, the bank converted Kenyan shillings (KES) to RWF and held them in a collateral account in Kenya. The bank issued a “Demand Guarantee/Standby Letter or Credit” that was guaranteed by the Kenyan bank’s subsidiary in Rwanda. The guarantee was shared with the end party in Rwanda. The logic of performing a foreign exchange conversion but not transferring the funds is to ensure that the local currency funds are available in the desired amount, if needed. This process took two days. Goal achieved!

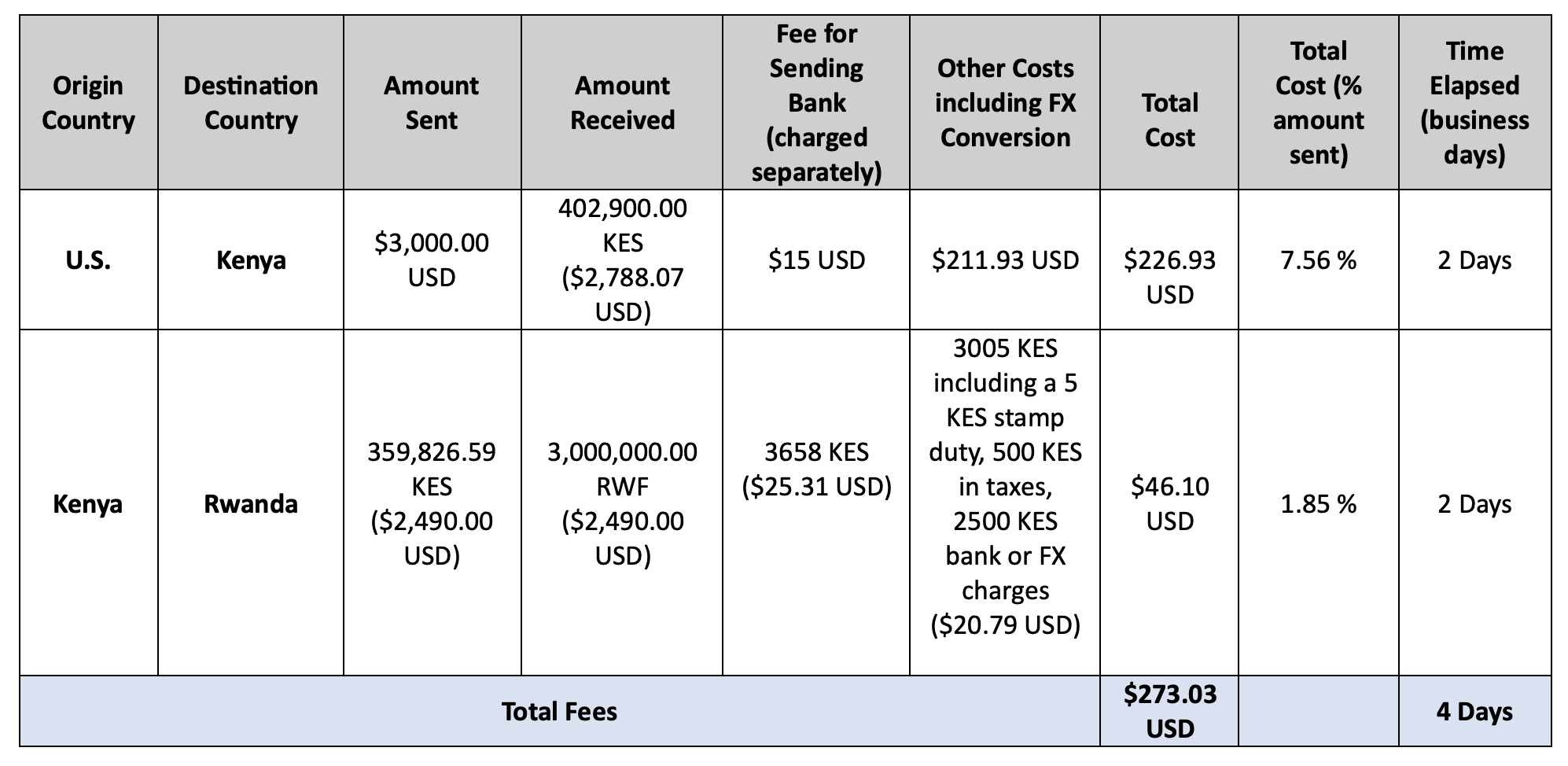

The financial journey to secure the bid security took two legs, four business days and consumed just over $273 USD in total costs. We broke down the details as best the information provided allowed. Fees are expressed in the origination currency with the destination currency[2] shown in parentheses.

Third step: getting the funds back

Following the bidding process, the bid security was cancelled, and the deposit was released. Victor confirmed release of the bid security and the transfer of funds into his Kenyan account in KES from the collateral account. We don’t have visibility into when the deposit was released or how long this process took.

Fourth step: returning the balance back to the U.S.

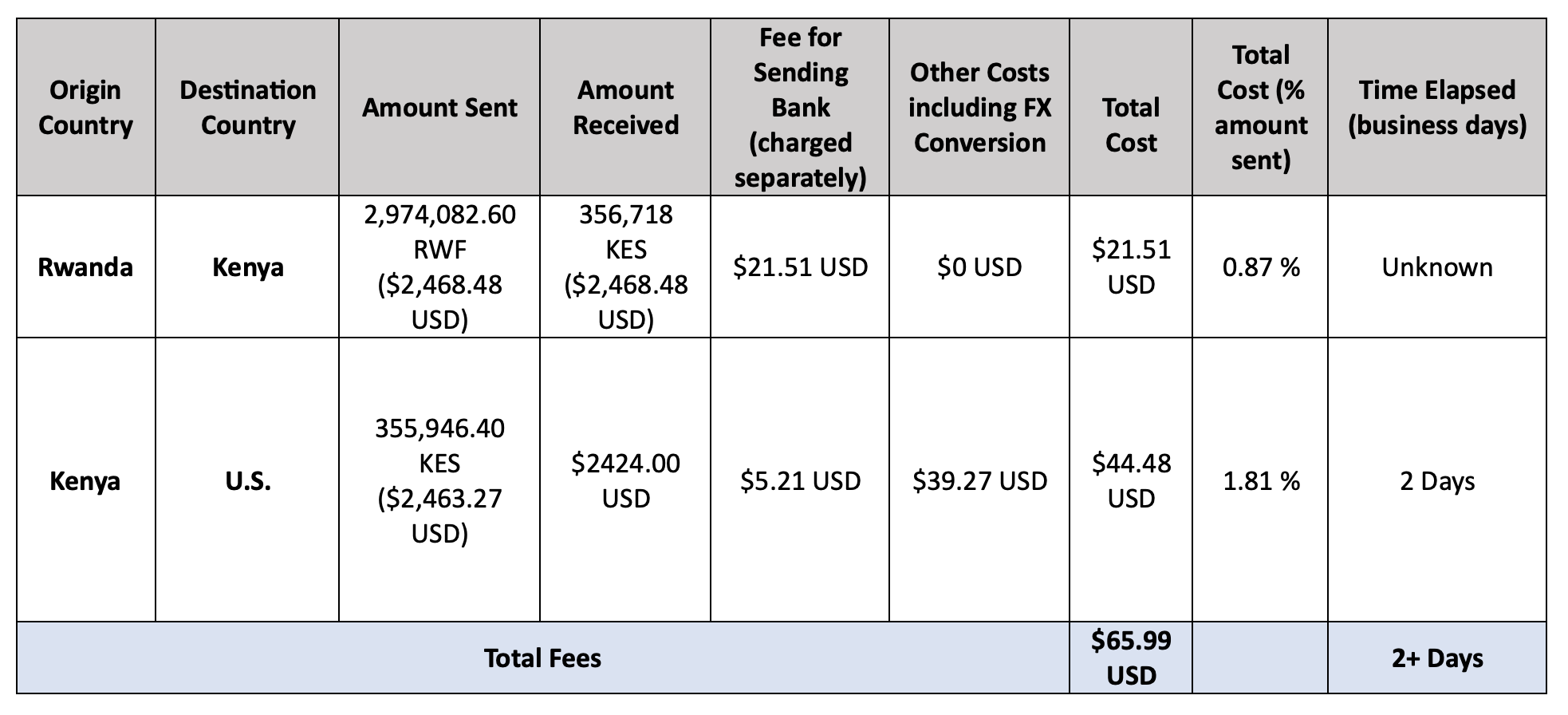

Victor soon transferred the remaining funds back to the U.S. In total, the financial journey home took more than two days’ time and consumed just over $65.99 USD in fees. Certainly, there was a noticeable difference between the overall cost out and back. We broke down the details as best the information provided allowed.

The Return: Getting funds back to the U.S.

The Result:

While we succeeded in our objective, the process demonstrated the persistent lack of clarity in international payments. The net costs of this effort was unknown walking into it. Ultimately, fees totaled $339.02 USD (and $251.97 USD that stayed with Victor, our Kenyan colleague). This is just over 10% of the original total value. The cost to get the money there was almost three times what it cost to get it back — and most of that was in the US to Kenya leg. Certainly, the distance was much greater (!) but they were roughly the same amount of money, both required a foreign exchange conversion, and took the same amount of time. Are these differences a reflection of a more liquid and widely available currency like the dollar being converted into a less widely available currency? Is the Kenya-Rwanda corridor used more frequently and therefore less costly? Lastly, it is important to note that we weren’t always provided a foreign exchange rate, so we can’t really know what foreign exchange costs versus other fees were in those cases.

Overall, the information provided by the service providers here was scant, the fees and costs varied widely, and even after the transfer was completed there was no “invoice” with transparent or clear detail on what had actually been charged. Fortunately, Glenbrook was able to absorb the fee and timing uncertainties. Still, the process was opaque. In some countries (including the U.S.) the law requires consumers to be informed on all these details. As a business, we were not afforded that information.

The good thing is that the process worked and our goal of making a bid security in a country far away was achieved. Nevertheless, this is not the process that it should be in 2023.

We also know that there may have been more economical options available, but we did not have the time to investigate them for this one-off need – a common issue for many businesses. But even if we could have saved money, would transparency have materially increased? Did any of the banks involved take advantage of the industry efforts to lower the cost of cross-border payments and provide more certainty? Were the compliance costs for the first bank materially more extensive and costly than the other legs? There are many questions that merit more explanation.

For the purpose of this payment, the two days it took to complete each leg of the journey did not materially affect the outcome (of getting the bid security and receiving funds back) because we were able to sufficiently plan ahead and did not depend on those funds for other business purposes. While it would have been helpful to hold onto those funds for a bit longer, not all cross-border payment needs have the benefit of time. Many small business, sole proprietors, and the 281+ million[1] of migrant remitters (and the beneficiaries that are counting on them for familial support) don’t have this luxury.

We can do better.

[1]: UN

[2] Conversion rates used for $1 USD: Kenyan shilling (KES): 0.00692 Rwandan franc (RWF): 0.00083