Highlights

It’s expensive to be a low income American, driven in part by the high cost of financial services available to such consumers. In this post, we break down where cost comes from, and how fintechs are changing the way working class Americans are able to access affordable financial products.

Fintechs have an opportunity to displace the traditional, high-cost services that target low income consumers. Through the consumer profiles we discuss in this piece, we can see that using fintech products instead of traditional services has a material impact on the financial wellbeing of low-income consumers.

Who Pays to Pay?

On the periphery of the payments ecosystem, a subset of Americans are paying millions of dollars each year just to transact. While payments professionals expect consumers to rely heavily on cards and ACH transactions, many financially marginalized consumers pay with cash, prepaid cards, and money orders. Many must take out payday loans for short term credit. The Financial Health Network estimates that in 2020 the financial services industry serving this market cost American consumers $255B.

But what does that number mean for individual consumers? And how can the industry improve the financial lives of at-risk consumers? To find out, we developed three consumer profiles and simulated the cost of financial services for each over the course of a year.

We take a look at how these three consumers get paid, save money, transact, and borrow. Our consumer profiles are informed by Glenbrook’s ongoing research into financial inclusion in the U.S. including conversations with stakeholders and desk research.

The “Conventional” Consumer

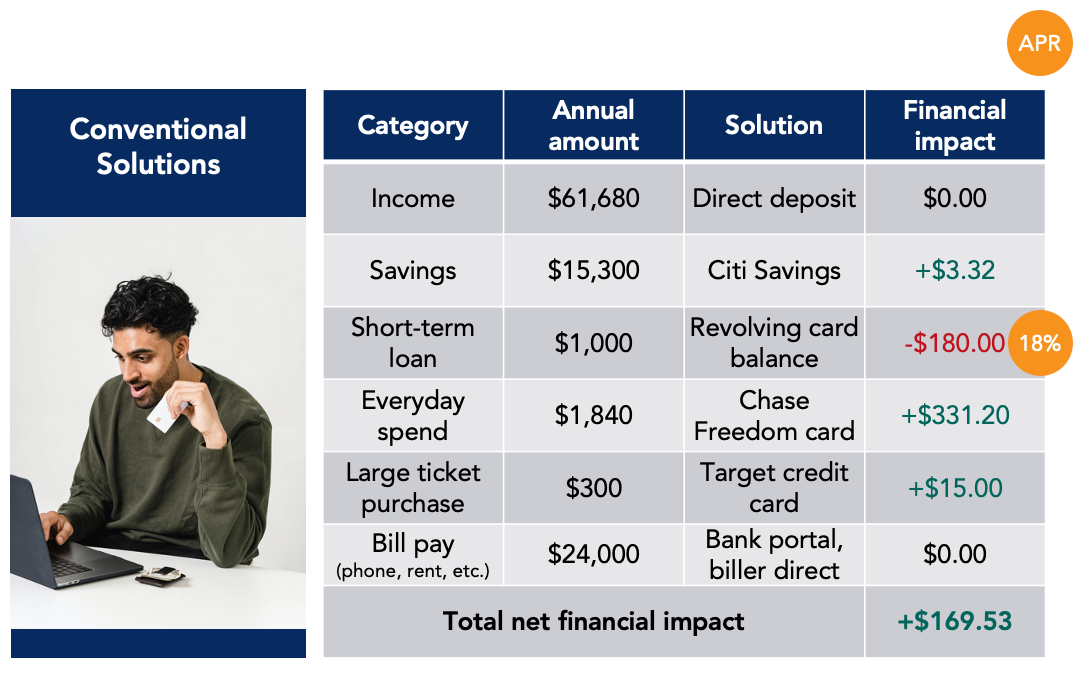

Figure 1: A year in the life of a conventionally well-served consumer

Let’s start by talking about the sort of consumer we, as payments professionals, are likely to have in mind as we develop new products.

Meet Andrew, a digital marketing professional in Los Angeles. He makes around $65,000 a year which is paid to him over the ACH network via direct deposit, costing him nothing to receive his paycheck. On top of that, he saves money in his Citi Savings account, which accrues very modest interest.

Even though he’s well-served, Andrew’s financial picture isn’t perfect. He relocated to LA to take his digital marketing job and needed to cover moving expenses. He had to take on a $1,000 revolving balance on a Capital One credit card. At an 18% interest rate, this costs him around $180 over the course of the year.

For everyday purchases, he uses his Chase Freedom Unlimited credit card and, after an annual spend of $22,000, earns about $331 in cashback rewards points.

Upon settling into his new apartment, he decided to buy an iPad for himself to catch up on reading for $300. He put this large ticket purchase on his Target credit card, and gets $15 back on the purchase.

His AT&T communications bill and his utility bill amount to $600 each month, and he pays them through Citi’s bill pay portal at no additional cost. He pays his $1,400 rent via ACH on his landlord’s website each month, which is also free to him.

After a year, Andrew has accumulated $169.53 in net income simply through his payments activity as illustrated in Figure 1.

The Traditional Underserved Consumer

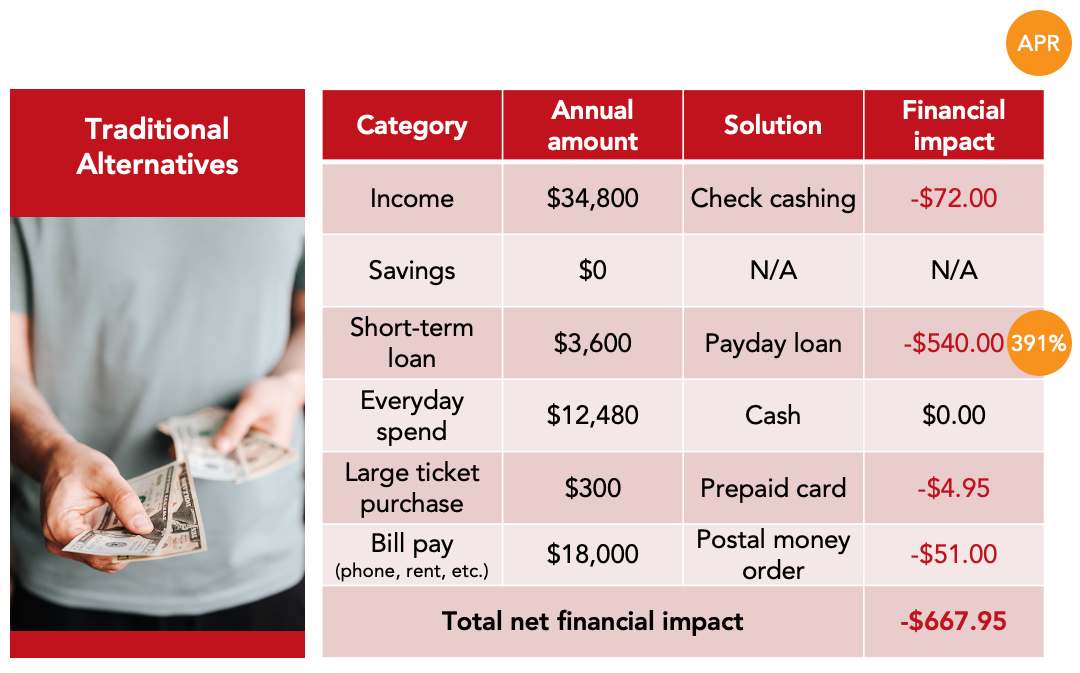

Figure 2: A year in the life of a traditionally underserved consumer

Next, let’s meet Ross, a low income consumer using traditional solutions who works as a line cook at a restaurant in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

He makes $35,000 a year and is paid by check. He receives his salary biweekly and pays $3 to cash each check at the local Kroger grocery store. Over a year, he spends $72 on check cashing.

To cover some expenses between paychecks, he takes out a payday loan. He typically borrows around $300 dollars on a two-week loan at CashAdvantagePlus (not a real store, but representative of the sort of local financial centers that dot low income communities). This local payday lender charges $15 on every $100 borrowed. So the total cost of the loan to him is $45. If, on average, he takes out one of these loans per month, he spends $540 over the course of the year.

He makes his everyday purchases using cash, so that doesn’t cost him anything over and above his cost for receiving cash from CashAdvantagePlus or Kroger’s check cashing service.

Like Andrew, he purchased a $300 iPad, although Ross is buying his as a gift for his boyfriend’s birthday. To take advantage of a sale online, Ross purchases a prepaid card at Walgreens for $4.95 in cash and uses this payment method to buy the iPad from an internet retailer.

Ross pays his bills by postal money order. His AT&T and utility bills are each less than $500, so those money orders cost him $1.25 each. His rent is $725, so that money order costs him $1.75. He spends $4.25 per month at the post office in order to pay his bills, adding up to $51 for the whole year.

At the end of the year, his net impact in Figure 2 shows that he has spent over $667 on financial services. At least partially because of this burden, he hasn’t saved any money. He’s also spent a lot of time going to different stores and service providers, time that’s really valuable if you’re working long hours or multiple jobs. And it costs money to get around, an additional cost that’s not reflected here.

The Fintech Consumer

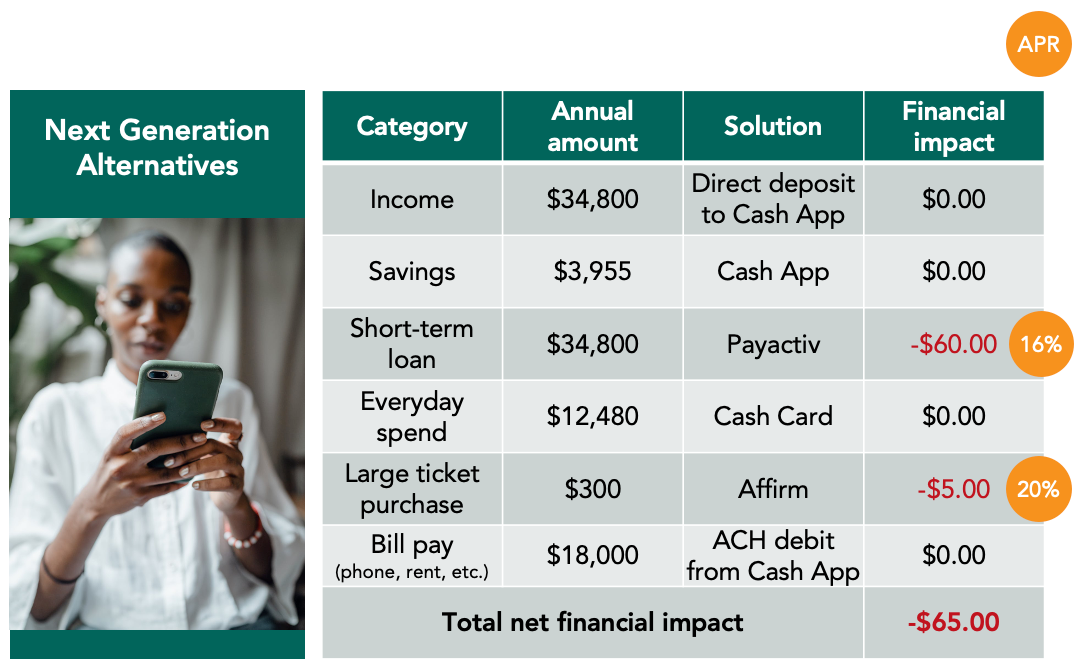

Figure 3: A year in the life of a consumer using new fintech products

Ross’s picture is bleak. He pays a lot and saves nothing. Now, let’s look at what the picture might look like for someone with the same salary but using fintech alternatives.

Meet Lena. She is a gig worker in Atlanta working for a (hypothetical) company called LocalDash, delivering goods from local stores to customers across town. She uses Cash App as her bank account, and receives her income via direct deposit thanks to the Lincoln Savings Bank account that sits behind her Cash App account.

Lena used to worry about when her paycheck would arrive in the mail and occasionally used payday loans to cover some emergency expenses in the past, but she can now access her funds two days early through earned wage access provider PayActiv. This costs her $5 a month, which is PayActiv’s membership fee. If you calculate that in APR terms assuming a loan term of two days, it amounts to around 16%, which is much more reasonable than what a payday lender would charge and lower than the rate charged on credit cards at this end of the market.

For her everyday spend, she uses Cash App’s Cash Card debit card product, and pays nothing to do so.

She also bought a $300 iPad to help with a creative side project she’s working on. Like Andrew, she purchases it at Target, but she checks out using Affirm. She takes out an Affirm buy-now-pay-later loan at a 20% APR over 12 months, which works out to around $33 in interest charges.

Thanks to the bank account that powers her Cash App experience (my colleague Laura touched on the mechanics of this in the previous post in this series), she’s able to pay at no cost her AT&T bill, utility bill, and rent via ACH.

As Figure 3 shows, she spends $65 on financial services over the course of the year, far less than the $677 that Ross had to pay. While Lena uses Cash App, Venmo or a neobank like Chime or Dave offer similar economics. Consumers in this space are savvy shoppers who might turn to Cash App for one set of services and Chime for another, or may stick to one provider to take advantage of the convenience of having everything in one place. Regardless, the end result is that underserved consumers now have greater opportunities to save, and fintechs are better positioned than ever to meet their needs.

What’s Next?

Fintech is not a panacea for the financial hardship faced by low income Americans. Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous communities remain disproportionately underserved by the financial industry. However, an increasing number of solutions offer bank-like services, often with FDIC insurance, direct deposit, etc. As we have demonstrated, these solutions are often less expensive and offer compelling value to consumers.

We hope that fintech providers will continue to create new affordable solutions for low income consumers. We’re watching this space closely to see how providers are stepping up to the challenge of better supporting financially vulnerable populations.

If this topic interests you, please reach out! We would love to hear from you.

About the Author

Justin Pituch helps lead Glenbrook’s research on financial inclusion in the U.S. Justin recently co-hosted a Glenbrook webinar discussing the potential for financial technology to alleviate the cost burden of financial services for low income Americans. Justin’s background is in treasury and banking consulting, but his first job was at a community bank in the Chicago suburbs.