Much has already been written about the Third Payment Services Directive (PSD3) and its anticipated scope following the release of the draft texts earlier in the year, but, understandably, mostly from a European standpoint. Arguably, PSD3 is likely to be more of an evolution than a revolution, with the transition from PSD2 to PSD3 less of a step than the advent of PSD2 itself. The prospect of its arrival does, however, provide the opportunity to take a step back and consider the potential implications and opportunities of this European regulation from a U.S. perspective.

Considerations for U.S. entities active or expanding in Europe

Firstly, let’s consider from the standpoint of any U.S. entities operating in, or considering operating in, Europe:

1. Core Compliance

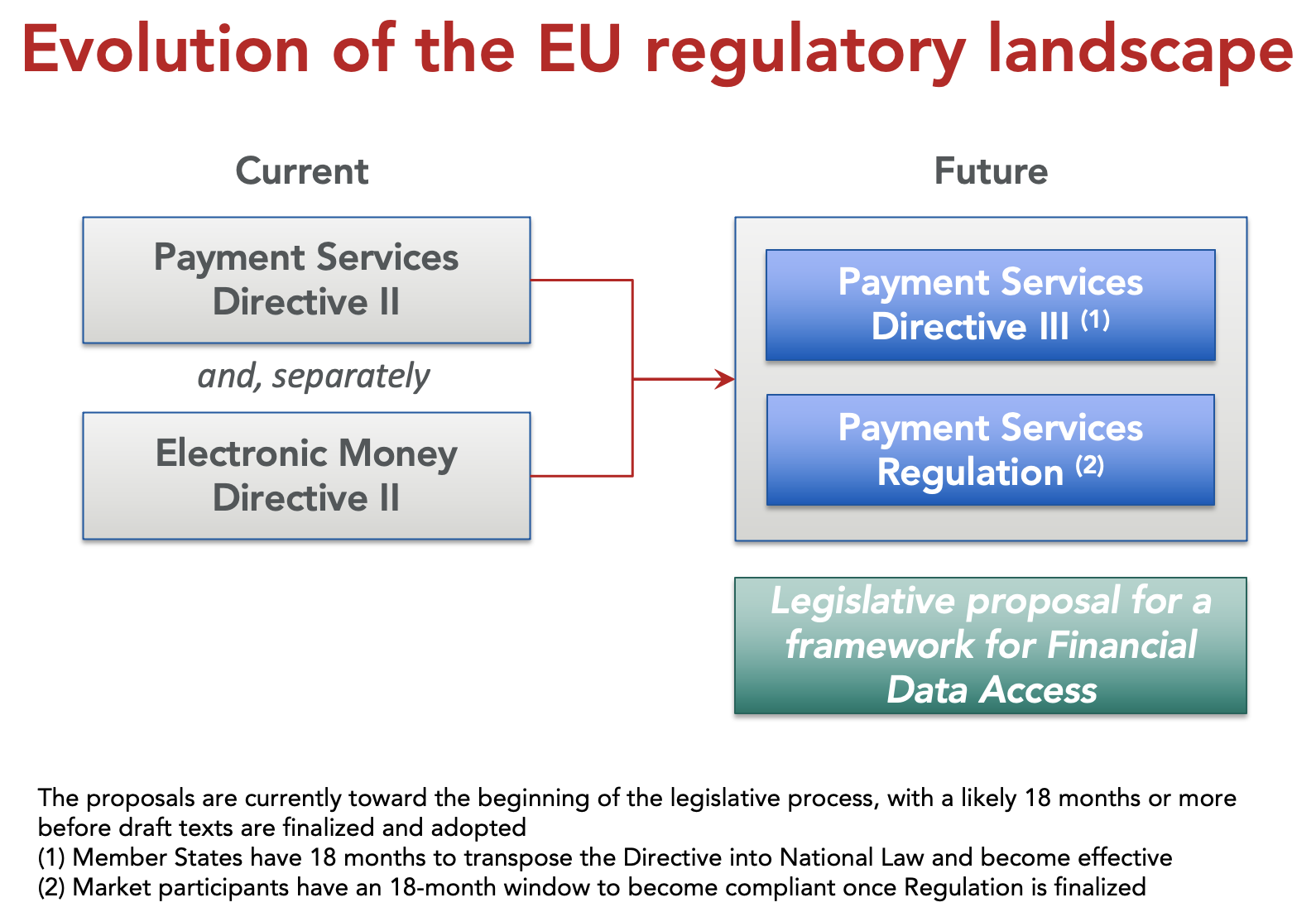

Clearly, any U.S. entity that currently has operations in EU will need to comply with the provisions of both the revised Directive, once written onto the national statue books of each member state, as well as the new EU-wide Regulation. The following diagram illustrates the evolution of this regulatory landscape.

Now, it is only the beginning of the legislative process: it will take many months before the current draft texts are finalized and adopted, for the new Regulation to become effective, and for member states to transpose the Directive into national law. So compliance with PSD3 will not be required any time soon, but any existing payment institutions or electronic money institutions will need to appropriately prepare for upcoming changes, which can take time, and apply for re-registration or re-authorization, with existing licenses only grandfathered in for 30 months after the Directive enters into force. Moreover, institutions will need to prepare for any nuances that may surface in discrete EU countries.

2. Further Operational Complexity or Strategic Opportunity?

For any company looking to expand their international operations, differing regional regulatory frameworks lead to operational complexity, and there-in the need for knowledge and expertise in the local jurisdiction with the associated increase in operating costs. The material differences in EU versus U.S. payments regulation clearly add complexity on the one hand, but does it give rise to strategic optionality on the other?

For instance, the EU regulatory provisions promoting; a consistent and established electronic-money regulatory framework, and the direct connection by non-banks into payment systems, could enable a U.S.-based payment provider to deploy a fundamentally different operating architecture, not reliant on sponsor bank arrangements or the need for multiple state-based money transmitter licenses. Alternatively, user-instructed third-party payment initiation, combined with third-party access to users’ payment account information, all via a dedicated technology interface, could open up novel new ways for merchants and billers to accept payment.

Hence, could the provisions of the EU Payment Services Directives provide U.S. entities with the option to consider and pursue fundamentally different strategic operating models for expansion into the EU, rather than simply replicating approaches deployed in the U.S.?

Considerations for the domestic U.S. ecosystem

The second lens through which to reflect upon the provisions of the aggregate Payment Services Directives is the domestic ecosystem within the U.S.. Whilst there is clearly no direct jurisdiction of PSD3, the read-across can highlight pitfalls to be avoided, opportunities to be garnered, and blueprints to act as points of comparison in light of the new CFPB Open Banking proposed rules.

3. Leveraging Solutions to Combat Fraud and Scams

It is fair to say that the UK and Europe are further down the journey of faster payments. Whilst that comes with benefits the U.S. is readily seeking to attain, it also comes with the pains and challenges associated with the exponential growth of so-called authorized push payment (APP) scams. These APP scams unscrupulously leverage some of the core underlying benefits that faster payment schemes deliver; real-time delivery of funds and irrevocability. Addressing that challenge, the provisions of PSD3 currently propose:

- The sharing of fraud-related information between payment service providers

- Protection for victims of APP scams where the fraudster impersonates a payment service provider employee

- The deployment of ‘Confirmation of Payee’ services with associated liability models

- Payment service providers to alert end-users to new forms of fraud, and to educate & train their employees on fraud risks and trends

Hence, is there an opportunity for the individual participants and the U.S. ecosystem as a whole to look to the experience, and the resultant mitigating actions, from across the pond and elsewhere to chart a different course as it pursues its own faster payments journey? This topic has been explored further by my colleagues Joanna Wisniecka and Bethany May in their post Stakeholders Respond to Fraudsters’ Affinity for Instant Payments.

Similarly, looking at card payments, the rate of card transaction fraud is somewhat higher in the U.S. than Europe, and furthermore is on a downward trajectory in Europe. There are undoubtedly many dynamics that contribute to that position, one of which is the framework for customer authentication. I doubt anyone would advocate the manner and original timeframes in which secure customer authentication1 (SCA) was implemented via PSD2, and the upcoming PSD3 will contain a number of clarifications and refinements to those provisions to smooth the rough edges. However, are there instances where U.S. merchants and issuers could leverage the existing and emergent technical solutions underpinning SCA to combat card fraud without adding undue friction to the customer experience?

4. ‘Blueprints’ for Fostering Innovation

From the perspective of financial data sharing, we have witnessed significant steps in the U.S. toward direct bilateral connections between financial institutions and open banking providers, moving away from screen-scraping. Although user-permissioning to access that data still requires, in some instances, the sharing of login credentials and, despite the efforts of Financial Data Exchange (FDX)2, those connections are not ubiquitous. Hence, today we see fragmented coverage and propositions.

In Europe, the provisions of PSD3 extend the current mandated, user-permissioned, market-wide access to accredited third parties to also include a dedicated technology interface for those third parties to access that account information. The CFPB’s proposed Open Banking rules also contain provisions for market-wide access to user-permissioned payment account data, through a developer interface with a standardized format, and thereby seeking to provide ubiquity of access whilst prohibiting screen-scraping.

However, neither proposed regulation goes as far as defining the actual technical standards for a standardized technology interface. In the case of the CFPB’s rules this is explicitly intended to be set by industry standard-setting bodies. In contrast, the deployment of Open Banking in the UK (whilst still part of the EU and adhering to PSD2), saw the establishment of an independent body; the Open Banking Implementation Entity, to co-ordinate the development of a single set of technical standards used by all participants.

Will the U.S. ecosystem reach standardized, full and consistent access through the current proposed Open Banking rules? Would the designation of a single standard-setting organization smooth interoperability and efficiency across the ecosystem?

For further insights on Open Banking in the U.S., take a look at From Open Banking to Open Finance: Redefining the Financial Services Landscape

Beyond data sharing, as faster payments usage continues to grow in the U.S. and the proportion of addressable accounts increases, the specter of use cases leveraging third-party payment initiation also increases. Some might argue that faster payments ubiquity is a pre-requisite for their existence. However, there is a converse argument (inspired by experiences in India and Brazil) that their presence could actually help to drive the adoption of faster payments, with non-bank entities creating novel use cases that complement the core faster payment rails and supplement value-added services like Request for Payment (RfP).

Equally, would streamlining access to those same payment systems for non-banking organizations (as envisioned by the Payment Services Directive) potentially alongside a harmonized regulatory framework for e-money providers at the federal level, foster increased innovation and competition in the payments ecosystem? Could the resultant use cases create the necessary end-user demand to accelerate the roll out of faster payments in the U.S.?

In summary, whilst PSD3 itself may be some way off, and its provisions an evolution rather than a step change, it provides plenty to think about from the perspectives of both U.S. entities operating or expanding into the EU, as well as the domestic U.S. payments ecosystem.

- Secure Customer Authentication: SCA is similar in nature to Multi-Factor Authentication. It is defined under PSD2 as an authentication based on the use of two or more elements categorized as knowledge (something only the user knows), possession (something only the user possesses) and inherence (something the user is) that are independent, in that the breach of one does not compromise the reliability of the others, and is designed in such a way as to protect the confidentiality of the authentication data

- As stated on its website; FDX is a non-profit industry standards body operating in the U.S. and Canada that is dedicated to unifying the financial services ecosystem around a common, interoperable and royalty-free technical standard for user-permissioned financial data sharing, aptly named the FDX API (www.financialdataexchange.org/about)