Time to Read: 7 minutes

Highlights:

- Design for low-income citizens is essential for successful eGovernment services

- Glenbrook has identified pro-poor implementation success factors: channel selection, payment methods, fee structure, and education

- Goal centered design brings the considerable benefits of eGovernment to all citizens

Expanding eGovernment Services to the Poor

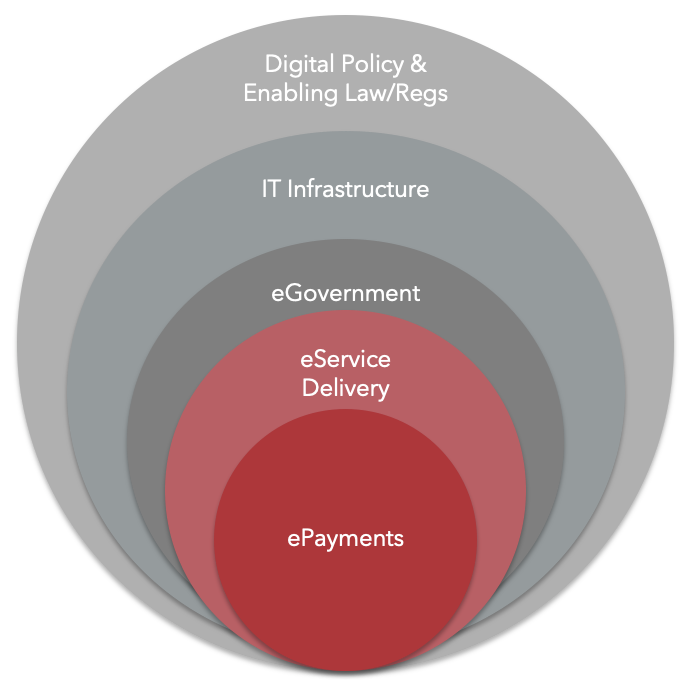

eGovernment, which includes both online service delivery and, where applicable, digital payment for government services, is no longer just for wealthy countries. To reach low-income families, however, eGovernment programs in developing countries must be intentionally designed. Otherwise, these initiatives risk being accessible only to wealthy citizens.

Design of ePayment solutions and eGovernment services requires planning and strategy regarding payment channels, citizen costs, and enabling programs (awareness and digital literacy) to ensure the substantial benefits of eGovernment reach all citizens.

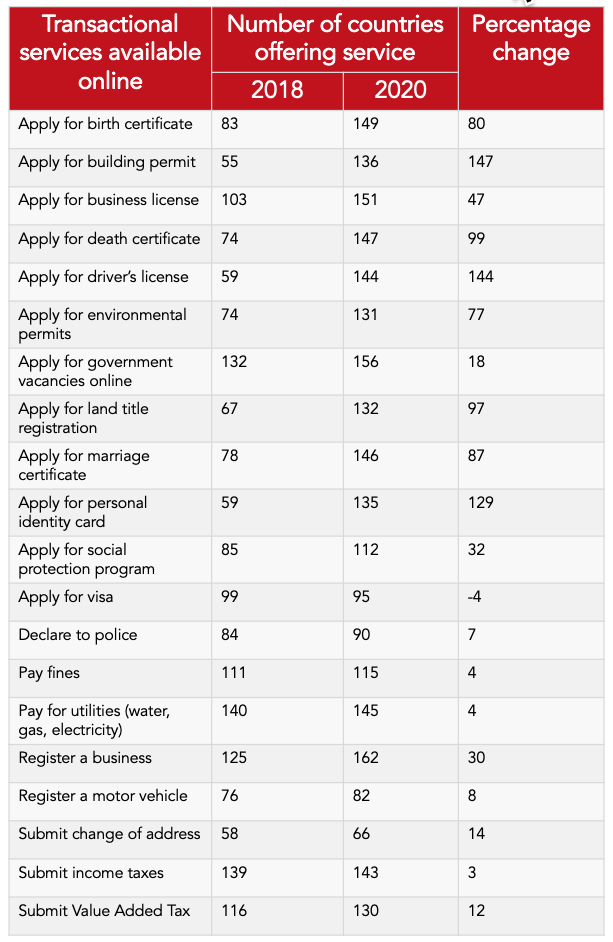

According to the 2020 United Nations E-Government survey, all but one of the 193 member countries have a national eGovernment portal to improve service public sector access and transparency. Online service delivery for government-to-citizen and government-to-business services grew rapidly between 2018 and 2020. UN member states provided, on average, 14 of the 20 services identified in the eGovernment survey (below). This represents a 40% increase over 2018 in online government service delivery.

Source: UN E-Government Survey, 2020

Source: UN E-Government Survey, 2020

Despite this very real progress, a recent benchmarking analysis of government ePayment services conducted by Glenbrook suggests that multiple eGovernment programs in the developing world lack solid pro-poor design. Our work also revealed a range of effective practices for service of low-income citizens by certain developing countries.

The following is a summary of our findings.

How Digital Access to Government Services Benefit Citizens

By digitizing both the service delivery process and the payment mechanism, citizens reap considerable cost and time savings. Through everyday phone-based interactions, they may access services and pay using familiar e-money systems.

Consider the Indian state Karnataka’s use of the MobileOne platform. It offers digital access and payment capabilities to over 1,000 government services. By using digital payments, users report the ability to earn an additional INR 1,000 – 3,000 (USD $10-15) a month because they no longer have to travel during business hours to government offices to transact in person.

For those living far from government offices, digital access expands accessibility. Senegal’s The Customs School provides a good example of eGovernment services. Once it digitized the payment process for entrance exam registration, registrations increased by 50%. The school noted that most of the additional registrations came from candidates located outside of the capital city, Dakar. Users of the digital platform estimated a per-payment savings of at least USD $8 on transportation costs.

Both the service delivery and the payment mechanism must be digital to

reap the full benefits of digital access to government services.

See Glenbrook’s post on the eGovernment – ePayment Conundrum

These successful examples of eGovernment service implementations can be powerful motivators for further use of digital financial services. Since all citizens, regardless of demographic, need to avail themselves of government services, provision of citizen-to-government digital payments increases the utility of digital transaction accounts.

The goal is to encourage signup and use of these accounts among the financially excluded. As some government payments happen on a recurring basis (e.g., utility payments in many countries), citizen-to-government payments may help citizens gain familiarity with digital payment options and thereby build confidence in the use of digital financial services in other contexts.

Three Implementation Best Practices That Promote Pro-poor Outcomes

Choose the Appropriate Channels and Payment Methods

To ensure success, governments need to be mindful of the existing level of technology access and comfort among their citizens. In countries with low smartphone penetration, rolling out an eGovernment portal exclusively through a smartphone-based mobile app only serves to benefit the smartphone-toting few. This basic design error reinforces the divide between wealthier smartphone users and the rest of the population.

To truly make eServices and ePayments available to all citizens, governments must assess citizen technology capabilities, i.e. internet/computer access, smartphone penetration, feature phones, etc., and then deliver appropriate channel solutions. Where necessary, governments must consider solutions that bring additional information communications technology (ICT) infrastructure to citizens.

Rwanda provides an example of a well-thought-out channels strategy. According to the ICT and Innovation Minister, mobile phone penetration stands at about 80%, while smartphone penetration stands at about 15%. When rolling out its one-stop-shop government services portal, Irembo, in 2015, Rwanda’s government made the decision to enable payment access via mobile money using a USSD menu. Users with feature phones can readily access and pay for government services. To further extend reach to those without any phone at all, the Rwandan government partnered with an existing agent network so that Irembo agents, for a small commission, can assist citizens in requesting and paying for government services.

System design needs to accommodate gender differences. A recent study by Caribou Data in collaboration with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation found that, among smartphone owners, women are more likely to favor USSD access to mobile money services.

Moreover, a persistent mobile phone gender gap persists in developing economies where women are less likely to own mobile phones than men. This suggests that enabling USSD access and agent access for eGovernment services and government ePayment may especially promote women’s access to government services. Excluding these channels could exacerbate existing gender divides in digital financial services.

Pro-poor Fee Strategies

That citizens save time and travel costs through digital access to government services is nothing new to governments. Some have tried to capitalize on this savings by charging fees to citizens for the convenience of paying digitally. These costs may be in the form of ‘convenience fees’ or ‘surcharges’ on the processing cost. The GSMA notes that citizens are willing to pay reasonable fees for transactions with government agencies. However, that willingness decreases for frequent or low value transactions. This suggests that citizens will choose a digital transaction only when the benefits outweigh the perceived cost of transacting in cash.

To encourage use, governments may consider foregoing convenience fees and absorb part or all of payment processing costs. Consider Rwanda as an example once again. The government absorbs payment processing costs and charges no convenience fees for use of its Irembo platform. For transactions done through its agent network, the Rwandan government covers the agent commission fee for a select set of common services such as birth certificate access. For less frequently needed services, the citizen pays the agent commission, however these fees are capped at 500 RWF (USD $0.50). By charging no or very low fees, the government has widened access to economic benefits for those at the bottom of the pyramid.

Awareness and Digital Literacy

A government may build the best eGovernment platform and establish the right channel strategy, but for real uptake of digital services, citizens have to know:

- That the service exists

- That there are real benefits for using the service

- How to access the service simply and reliably

Awareness and digital literacy campaigns must be prioritized to educate the target users.

Governments have historically struggled with raising sufficient awareness for their ePayment channels. A landscape study on person-to-government payments in developing countries by Karandaaz found that insufficient investment in consumer awareness remains a key barrier to consumer uptake of eGovernment services.

Know Your Citizens

While some governments simply do not prioritize investment in consumer education, others may be investing ineffectively. Karandaaz discovered, for example, that almost none of the organizations studied had conducted market research to determine the most effective messaging for their outreach efforts.

Assumption of responsibility for awareness raising can also be a barrier. Is it the government’s responsibility, or the responsibility of the payments service providers, or both? Successful efforts often involve a collaboration among stakeholders with both government departments and payments service providers sharing in the effort.

When the government of Kenya launched its one-stop-shop eGovernment portal, eCitizen, in 2014, it enlisted the support of mobile money providers in the market to promote use of eCitizen through the mobile money channel.

Conclusion

Governments are supposed to serve everyone. Yet all too often, for citizens residing far from the capital city or in rural areas, government services may be prohibitively difficult to access. eGovernment solutions that offer both digital service delivery and payment capabilities can bring government closer to the people. They also promise meaningful, positive impacts in terms of time and cost savings for users.

However, to reach all citizens, especially those with limited technology access, who may be lower-income, and less familiar with digital financial services, governments will need to be intentional in their implementation or risk exacerbating existing divides.

Key steps in effective system design include:

- Selection of appropriate digital channels and payment methods to reach all citizen regardless of their level of technology access

- No- or low-costs for citizen-to-government payments and citizen benefits access

- Investment in education through targeted customer awareness and digital literacy campaigns so citizens know why and how to access digital government services

Built with these principles, eGovernment programs have a better shot at reaching their full potential in bringing government to the people.

If you are a policymaker, infrastructure provider, or financial services provider thinking about any of these challenges, we would love to hear from you.

About the Author

Laura Dreese is a Senior Associate with Glenbrook’s Global Practice. She comes to Glenbrook with 8 years’ experience working in microfinance credit and technology solutions on a global scale. Laura holds an MBA from Columbia University and a BS from the University of Wisconsin Madison.