In this episode, Yvette Bohanan and Chris Uriarte sit down with Eyal Elazar, Head of Product Marketing at Riskified, to discuss policy abuse trends and the implications of consumers and professional criminals increasingly engaging in these schemes.

You can listen to the full podcast using the player below or continue reading to learn more about this topic.

What is Policy Abuse?

Policy abuse, a form of first-party fraud, occurs when a customer – whether legitimate or a professional posing as a legitimate customer – manipulates a business’s policies for financial gain.

A newly released 2023 Riskified survey of over 300 merchants found that 90% of online merchants believe policy abuse is a significant problem for their bottom lines.

Source: Riskified, 2023

Policy abuse can take various forms, including:

Return Fraud: Exploiting a business’s return policy by returning used or stolen items for a refund or store credit. Organized groups sometimes engage in return fraud schemes, resulting in significant financial losses for businesses.

Coupon Misuse: Using coupons in ways that violate the terms and conditions set by the business. Examples include photocopying coupons, using expired coupons, or combining multiple coupons inappropriately.

Offer Exploitation: Creating multiple accounts or using fraudulent information to take advantage of discounts, freebies, or other offers intended to attract new customers.

Item Not Received (INR): INR occurs when a legitimate customer does not receive a purchased item. INR can be used in cases of third-party fraud when a customer has a package stolen from their doorstep or when the item they were expecting is not shipped to them. However, when a legitimate customer receives the item but claims they did not in order to avoid paying for it, then INR becomes first-party fraud.

Reseller Abuse: Using automated bots to purchase items from a retailer (or manufacturer) to create false scarcity and resell the items on a marketplace at a higher price. The business suffers rapid inventory depletion, resulting in revenue and reputational impacts, along with being disintermediated from the customer. The customer who purchases through the reseller suffers, too, by paying more than they should for the product.

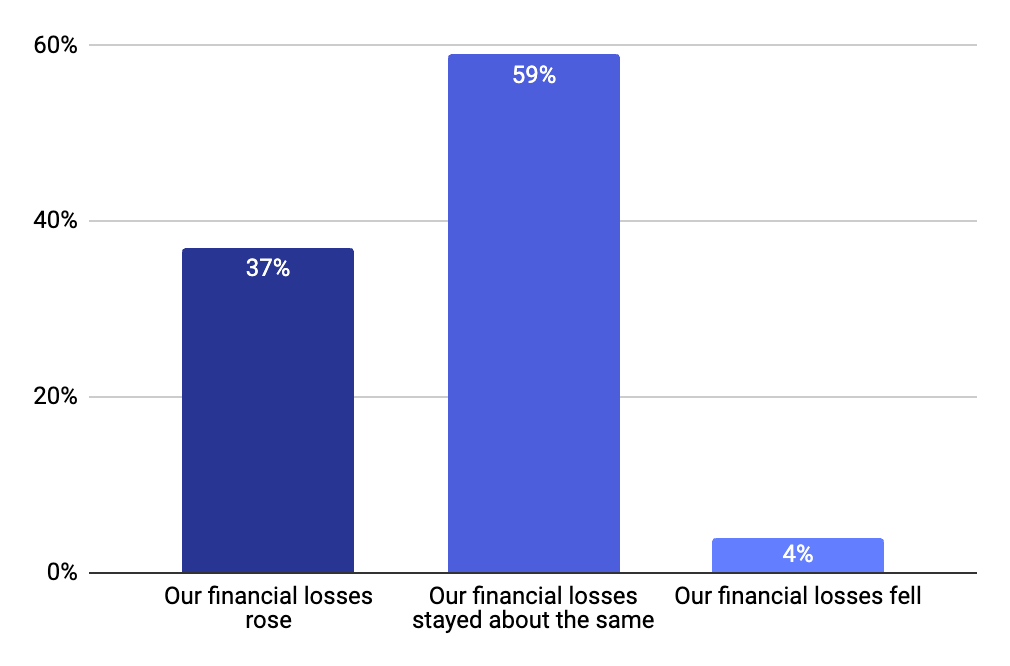

While some forms of policy abuse have held steady for the past year, several are on the rise. In a recent Riskified survey, 37% of business respondents noted that return fraud is increasing, 57% have seen an increase in Item Not Received (INR) fraud, 38% have seen an increase in promotional code abuse, and 45% have seen an increase in reseller abuse.

Why is Policy Abuse Hard to Prevent?

Given the wide range of policy abuse schemes and that an estimated 30-40% of policy abuse cases involve legitimate customers, it is not surprising that fraud controls designed to mitigate third-party fraud (where the customer or account holder suffers a financial loss) are not successful in detecting policy abuse. Moreover, many policy abuse schemes, such as coupon fraud, do not result in a chargeback – historically an essential confirmation tool for detecting fraud patterns, blocking bad actors, and training models.

What Should Businesses Do To Curb Policy Abuse?

Because the symptoms and financial impacts of policy abuse show up in various places in an organization, businesses should create a cross-functional team to discuss all forms of policy abuse. Consider a team that includes risk management, finance, legal, customer support, marketing, and logistics. As appropriate, product managers, software engineers, and information security team members may be included to discuss trends, issues, and potential improvements to controls.

Data that reflects a 360-degree view of marketing programs and customer accounts is critical to making cross-functional conversations actionable. High-level data that pulls through a customer journey – for example, sales, returns, chargebacks, and refunds related to a specific marketing promotion – is a good place to start. Be prepared to segment data further to see patterns that will unearth actionable information. Segmenting by payment methods, geographic details (such as zip code), and customer demographics will be important to ensure controls are specific enough to protect good revenue. Getting to actionable insights requires everyone to focus on the 360-degree view of the data and resist the urge to look solely at gross sales. Focusing on the “top line” can result in limited thinking about the actual revenue a program or product is generating, allowing fraudulent schemes to perpetuate.

Once a new control is identified, creating or enhancing automated controls focused on specific policy abuse schemes enables scalability and tuning for a particular form of abuse. For example, models and tools that detect reseller bots will identify bot versus good customer activity. Combining these automated controls with refreshed manual controls, such as updated customer support procedures and policies, creates a comprehensive, measurable, and tunable response to specific risks.

Policy Abuse is Here to Stay

With younger demographics more prone to believing policy abuse is acceptable behavior and more organized rings participating in first-party fraud schemes, businesses must recognize that policy abuse is here to stay and act accordingly. Getting the conversation started internally and looking closely at your data is the first step in mitigating the losses and risks associated with this first-party fraud.

Yvette Bohanan:

Welcome to Payments On Fire, a podcast from Glenbrook Partners about the payments industry, how it works, and trends in its evolution.

I’m Yvette Bohanan, a partner at Glenbrook and your host for Payments on Fire. Today’s episode shines a light on policy abuse. In case you are unfamiliar with the term, policy abuse is a form of first party fraud. First party fraud simply means that a business, not a consumer, is the victim of the fraud scheme. Policy abuse occurs when a business’s policies related to returns, offers or coupons are deliberately manipulated for the consumer’s financial benefit. You may be surprised to learn that policy abuse is illegal in some states and can carry fines or even jail time. Policy abuse often begins with a legitimate purchase. Let’s consider a renting example. In this case, renting is the act of purchasing an item with the intent to use it once and return it as if it was unused. Say for example, your team makes the FIFA World Cup finals and you decide to throw a watch party, suddenly your 32-inch television doesn’t seem up for the occasion, so you purchase a 70-inch TV for the big event and then return it after the game.

The store’s policy is no returns on the electronics unless they do not work properly. You return the item saying the picture was blurry, which it wasn’t. That’s renting. So just how big of an issue is policy abuse? Like so many payment statistics, it depends on who you are talking to, what they are measuring and how they’re measuring it. The National Retail Foundation’s report on customer returns in the retail industry reported that of the $4.95 trillion in US merchandise sales in 2022, $816 billion worth of merchandise was returned. Of this roughly 10% or $84.9 billion was return fraud, policy abuse. That’s just retail merchandise return fraud, but policy abuse shows up in non merchandise returns, creating fictitious email addresses to get more than that one month free trial offer, applying single use coupons multiple times, altering receipts, and returning items that were picked up off a shelf or disputing a subscription after using the service.

The list is long and the number is larger than the $84 billion in the US and larger globally. According to the 2023 CyberSource global fraud report, policy abuse ranks at the top five fraud attacks experienced by merchants in North America, Europe, and LATAM. Here’s what’s really caught our attention, many consumers think this is okay. In a recent Riskified survey of 1000 consumers, 45% reported that they have committed some sort of light fraud. In other words, all the categories of return fraud and policy abuse surveyed and one third of all respondents had opened a new email account to use promotional offers more than once. Why the shift in consumer’s attitudes? And what are merchants thinking and doing about all of this? Joining me to discuss these and other aspects of policy abuse is my colleague and Glenbrook Partner Chris Uriarte. Chris, welcome back to Payments on Fire.

Chris Uriarte:

Hey, Yvette, good to be back here and always good to be back here to talk about fraud and risk management, so I can’t wait.

Yvette Bohanan:

This will be a good one too. So let’s introduce our guest. We are delighted to have Eyal Elazar head of product marketing at Riskified joining us for this episode. Eyal, welcome to Payments on Fire.

Eyal Elazar:

Hi Yvette. Hi Chris. Thank you so much for having me.

Yvette Bohanan:

It is wonderful that you’re here and I just have to start. We often start this way by asking our guests how you got into payments, and here you not only fell into a payments rabbit hole, but you fell into the payments risk management rabbit hole. How did that happen and how did you make your way to Riskified?

Eyal Elazar:

Funny story. I’m actually a second generation payment risk fighter. My mother used to work at MasterCard. She was in charge of international fraud, back then it was card present, I won’t give away my age, but yeah, they were dealing with a lot of different types of impact. To be very honest, I only realized that after six months working with Riskified that I can actually share stuff with my family and they understand what I’m talking about. So that was a coincidence. I wouldn’t say that drove me into payment fraud. I’ve been working with the large enterprises for the last 15 years or so, not just on payments, but overall how they can use different softwares and solutions to leverage growth opportunities and improve efficiencies. And I joined Riskified about a couple years back, about just over two years ago.

Now, a lot of your listeners may know Riskified, they’re a leader in e-commerce risk intelligence, and while we’re mostly associated with chargeback risk management, we actually do a lot more and today we’re going to talk a little bit about that. I think I had the privilege of joining the company just when we started expanding into this super interesting domain of policy abuse and I had the luck to see how this evolved during the last couple years and it’s a super interesting topic to discuss.

Yvette Bohanan:

It’s timely and super interesting, but I’ve got to say a shout-out to your mom and the fact that you are second generation fraud fighter, if you will, is, I think, a first on this podcast and probably pretty unique overall. So in MasterCard, international risk management, no less. So that’s a huge area she was in. We’ll have to invite her on sometime, that would be cool. That would be very cool. Okay, so let’s get into this topic here for today’s episode and start by looking at and discussing some of the data that you collected. You all at Riskified did a survey in 2022 and one of the things you found out was that 45% of consumers admitted to committing some form of policy abuse. Was that a surprise?

Eyal Elazar:

To be very honest, it was not. I tend to think that we’ll see this number growing. I have a close friend, shout out to Diana, and she has a term that she claimed, which is policy abuse is a monster of our own creation. We’re in this rat race to making things as accessible and focusing so much on customer experience that they made it so easy to circumvent the policies and create serious losses without having to invest anything. If you think about it, how many websites can you actually buy without getting a prompt: wait before you actually pay me, is there a promo code that you want to use? Wait, wait, wait. Before you’re ready to go, do you maybe want to sign up and get an additional 10% or 20% even if you already signed up? And if you want to check on your order or even if you got the order and you want to look at it, some merchants already have a button if you want to free return or anything like that. It’s as if someone’s encouraging you to exploit their policies. And this is also like a slippery slope.

Yvette Bohanan:

It’s done in the name of growth, it’s done in the name of increased conversion in the card not present space specifically. There’s a lot of tentacles that we’ll get into on what’s first party fraud, what’s policy abuse. This is a very slippery slope, in a lot of respects. But what you’re saying is actually very interesting. I like this monster of our own creation because it kind of is, people are very pressured into growth. We’re measured on growth. The street measures you on growth, everybody’s looking at growth and one of the hardest things is being in a risk management team and trying to convince a leadership team in the organization that the fabulous numbers they’re reporting to the street aren’t as fabulous as they think they are because there’s a lot of abuse going on. What’s driving this? You said, you think that this is going to increase and you weren’t really surprised. What are you seeing in the patterns? What are you seeing in that data of the survey that makes you think this is only going to get bigger?

Eyal Elazar:

So I think it’s a combination of a couple of things. First of all, I think more and more people get the taste of it. As I mentioned, you are almost encouraged to try it out. You are almost pushed to get another signup and you hear about people doing it. It became more and more common. Now think about it with card and fraud, eventually you have a person that needs to get their hands on something illegal, someone else’s credit card or account. Here, people don’t always look at it as a bad thing. This could start off with someone getting a package or sorry, not getting a package, calling customer service, getting their money back, and then they get a package the day after they get a refund. Do you think they call them back and say, “Oh, I want to pay you again?” They don’t and they get a taste of it.

The same with, you know what, you get a 20% discount on your favorite brand, it’s nice. Then you have another thing that you forgot to buy, but “Oh, I lost the discount. Why don’t I just use another email?” I mean, it’s okay. I could have bought it a month ago when I used it initially. So this is the one thing, first of all, once you get a taste of it and you start being in that fudge area when you’re not really doing something bad but you’re not doing something good, it’s a problem. And this is why I believe it’s growing.

But also if you look at the stats behind our survey, like you mentioned, 45% average are actively abusing policies online. But if we look at the age distribution, we find a strong correlation to a younger generation. So again, while the average is 45%, if we look at ages 18 to 29, we’re at 65% and we look at 30 to 44, we’re at 51%. So if more and more people are trying and we see that the younger generation have a taste for it, then it’s only a matter of time before the ones who do it once, maybe twice, start doing it more occasionally, then maybe start doing it systematically. And there are ways to do it in a far more sophisticated way, but this is why I see this phenomenon will not go away anytime soon.

Chris Uriarte:

Yeah, you’re hitting on something there Eyal that was going through my head is this is a bit of a gray area when you look at taking stolen credit card information and making purchases with it or identity theft, it’s very clear. People know that that’s bad, that’s illegal. There’s clear rules and regulations around that, but some of the things that we’re talking about here really fall into this gray area. And I think the other thing that you’re hitting on is I feel that some of the perpetrators look at this as almost like a victimless crime where if you steal someone’s credit card you know that perhaps you’re defrauding someone or inconveniencing someone. And I get the sense with these sorts of actors that they’re saying, “Well what’s the big deal if a particular retailer who’s making billions of dollars or tens or hundreds of million dollars loses a little bit of money on my little package here?” And I suspect that’s part of the mentality here as well.

Eyal Elazar:

This is so spot on. As we learn this topic internally, we always scan the dark web and the different forums and discussions online and what we see is alarming. You mentioned, you know what, big companies can afford it, maybe it’s okay, it’s more than that. We see people writing “these companies have it coming”, they always almost see themselves as doing something good rather than questioning if it’s bad. They’re saying they are making the world a worse place, they’re making tons of money off of weaker populations and I don’t see a problem with me taking the profit instead of them. Now again, we don’t see that every time.

A lot of people are saying, you know what? They can afford it, but definitely this is where you feel like it’s an individual against this huge conglomerate. And you know what? So I got this $100 item for free. That’s okay. Especially if you’re a good customer and if you’re honest, I always share this full disclosure, even before my days at Riskified, I signed up to a couple of websites twice before I was a really, really good customer and I bought from certain brand a lot and after a while I was prompted with, would you like to get 20% off if you sign up? And I really signed up like a while ago, so I did another email that I had and did that, am I a bad person? Maybe based on today’s standards, my standards today, maybe back then it made perfect sense. I don’t know.

Yvette Bohanan:

Well, and I think people keep getting fed these promo offers and the promo engines aren’t quite sophisticated enough to pick up the fact that you’re already a customer. They just keep offering. And so at some point I can see some people will be like, okay, I’m going to take up this offer. But there’s also this sentiment that I think when you were talking about this notion of this monster of our own creation, sometimes it’s more costly for a merchant to process a refund and take something back. It’s just not worth it. Even if you call up and you say, “I just don’t want this, I want to send it back”, they’re kind of like, “We’ll give you the money, just keep it. It’s a low threshold. We are not going to be able to resell it.”

For whatever reason, the policy has sort of trained people that x percent of the time they’re just going to tell me to keep it anyway. So I think that’s another angle to this that people aren’t quite cognizant enough of when they’re making these decisions. Maybe there is more overhead associated with processing the return and getting the item back. Even if you have to dispose of it or something, because you can’t resell it for whatever reason.

You’re kind of training people that it’s a blanket sort of issue that they can kind of just expect you to say, keep it and don’t worry about it and here’s your refund. So I think there’s a lot going on here that’s been happening over several decades, particularly with card not present coming on the scene. Of course this has always occurred in card present too, but different forms of first party abuse or policy abuse. I always had that example of the person finding a receipt for an item on the parking lot outside of the store and they pick up that receipt and they walk in and they pull something off the shelf and they go over to the return counter and they get money back for something they didn’t buy. The account holder, the card holder isn’t getting any harm there. They didn’t actually steal their card, but they’re getting some money back at the return counter. And merchants caught on and changed their policies, a lot of them. But that was happening decades and decades ago before any of the card not present world was even invented.

Eyal Elazar:

Yeah. Absolutely. I think that even in some cases you didn’t have to have a receipt. You mentioned the threshold. If this was a low dollar item, you could just take something off the shelf and go to the cashier and just, you don’t even have to exit the store. You take it and you put it back and you say, “I’m here to return it. I’m sorry I don’t have my receipt.”

Yvette Bohanan:

Yeah, so there’s a lot to that, right? So there’s been this sort of laxity on the part of the merchants, there’s been this interest to convert more customers at the card not present conversion checkout page, bring on more people. There’s been a lot of reward for that high level GMV number that everyone looks at. Is it global? Are you seeing this everywhere or is this like a US thing or a regional thing or is it really kind of all over the world?

Eyal Elazar:

Oh, it’s definitely global. You mentioned our previous survey. We actually have another survey coming up mid-September where we surveyed hundreds of merchants across the world and the results are very conclusive. This is a global phenomenon. Naturally there are nuances between specific regions, some things are more common in different places. There’s also a little bit of the legal aspects in certain geographies, especially in Europe where you’re not even allowed to prevent someone from engaging in certain activities. But what I do think that we need to remember when we talk about a global phenomenon is, and it’s also what you mentioned about the cost of return, that when a merchant in the US is selling to someone in Europe and they want to send the item back, how much would that cost the US merchants? And then I think we get into another form of abuse incentivization where as you mentioned, sometimes it’s not even worth getting the item back.

So we have merchants taking almost random threshold, “Oh you know what, anything under $50, I’m not going to bother my time in getting it back.” What happens there is that that becomes the new norm for abusers. You know that if it’s under $50, you don’t even have to try and lie. You just want to tell them, you know what, I don’t really want it. They’ll tell you to keep it and just offer to give you your money back. Oh, you know what? Worst case you’re going to get some type of credit. It’s free money. So this is something that is extremely common and I think that a lot of merchants, they set this type of one size fit all policy, anything under $70, just keep the item. They think that it’s in their best interest because it encourages some type of efficiency when in fact it opens the door for even more abuse.

Chris Uriarte:

Yeah, it’s very interesting and I think as we see the nature of the goods that people are purchasing online now is starting to skew heavily in the direction of digital goods more and more compared to say 10 years ago or 15 years ago. So I would suppose if you’re a retailer that’s selling digital goods, it’s probably more likely that you’ll just refund someone who asks to request when your margins are very high on digital goods in a lot of cases versus say a physical good. Whereas you said you have to figure out how to get that good back, how to exchange it, how to ship it back, which has a very, very high cost associated with it. So you probably see different behaviors that are occurring based on what the merchant is selling, whether the point that you brought up, whether they’re selling cross border internationally or whatever the case is as well, right?

Eyal Elazar:

Yes. So while this is a very global phenomena and abuse is a piece to everyone, we see the different verticals definitely have different challenges. This could be services that could be inclined to get promo abuse like first month off or anything like that subscription. And these could be luxury good items or high end fashion that could have a lot of resellers that are trying to maybe even buy certain things in a US promotion and then selling them in a different geography and making a good money and creating this type of new competition to the same merchant within that geo.

And naturally everything regarding revolving physical goods and refunds and returns. It’s a mess with some, it’s more of didn’t get the item. Some may be returning fakes. We can do an entire podcast of me sharing some of the things we see on dark web anywhere between manipulating shipping labels and using Disappear Ink to print shipping labels. So by the time someone wants to do something with your empty box is no longer there. But truth be told, the easiest thing is still just picking up the phone and telling someone you never got it.

Yvette Bohanan:

Yeah. So let’s double click into this. This is kind of interesting. I think people would like to hear a few of these schemes, but what you’re really touching on, just to clarify this is we’re kind of moving from the customer who gets tempted away from the straight and narrow and they start doing this and they get by with it or they get trained in a sense that it’s okay, to actually people with very professional techniques, shall we say.

I’d love to hear about the disappearing ink a little bit and explain that to people because a good one, there was just a big story about a month ago, I think in the newspaper about the woman that they caught who was doing the luxury handbags scheme. So if you want to chat about that and maybe one or two others, but what are you observing when you talk with merchants and look at this activity on the dark web? Are the merchants really seeing a lot more of this formal fraud scheme type abuse as first party fraud versus errant customers? Or how’s the breakout looking?

Eyal Elazar:

It’s very interesting. First of all, you mentioned this being top of mind for merchants, and it’s so important that merchants will get educated and understand the different things that they could be experiencing. Because first of all, from a cost perspective, the cost of policy is usually fragmented across different departments. Some of it is appeasements, customer service, some of it is refunds, some it is about logistics. Quantifying the losses is wounding, but also without a chargeback that will tell you something happened here, how do you know? And only when you start to work closely with fulfillment and logistics is where you can actually find these type of gems where it’s like, “Oh, it’s not just, oh, what’s here? This is an empty box.” No, this is a pattern. So the type of things that you could see, and I think again, physical goods is very interesting and the empty boxes, now I’m saying empty boxes, but there’s a variety of things that people send in boxes between rocks and newspapers and plants and just various types of gifts.

Anything except the original product, there is a form of abuse called fake tracking ID, which is label manipulation. Someone will then go and just edit the actual original label. So it will be scannable, FedEx will be able to scan it all way back, but the actual package will not be identified and could not be correlated to the original order. So they use an empty envelope or something within an envelope stick this manipulated label on FedEx, then scans it, and then they say, you know what? I send it back. I have proof of delivery, someone scanned it, but the warehouse never got it. I just need to get my money back. This is not me. This is on you.

And it’s really hard to find these if you’re not looking for them. And again, disappearing ink, it’s not that common. I think it’s very interesting, but it’s not that pragmatic to print the shipping label with the disappearing ink and you stick it on an empty envelope or an empty box, someone would scan it and by the time it reaches the warehouse, the ink will fade away and it’s a blank label. And again, it went missing.

Yvette Bohanan:

Did you hear about or have you seen the dry ice one that’s like that where people were putting dry ice in the package? So when the FedEx was actually weighing, it weighed out and by the time it got there it was nothing. It was literally it evaporated.

Eyal Elazar:

People get so creative. I love it. I love it. It’s like watching, if it wasn’t sad, it was funny, it’s like a comedy show. Oh, you have to look at this. You wouldn’t believe what we just saw. But I want to address something that you just mentioned. Now we talked about the different types or severities or the spectrum of abuse. There are those who will do it once. There are those who will do it twice. There are those who will do it accidentally. “What? Oh, it turns out that someone did pick it up. It was my neighbor the next day.” But then we see that it becomes very intentional. I mean, there’s no way for us to open the label, manipulate it and thinking that we did something which is maybe okay. And it gets far worse when you look at the dark web, we see specific, almost every type of merchant is being targeted and there is very clear guidelines how to abuse different merchants.

Yvette Bohanan:

Manuals being sold or instructions being sold on the dark web of how to do this for this particular merchant.

Eyal Elazar:

Yes, yes, absolutely. And there are professional services, people who are telling customers, consumers, whenever you want to buy this specific merchant, if you buy up to 2, 3, 5, 20 orders a month up to $1000, just send me your orders. I’ll talk to them. I’ll make sure you get your money back. Then I’m taking a 20, 10% fee on whatever I give you back. You don’t have to do anything. Just send me the details. I’ll make sure you get your money back.

And it’s a marketplace. You have people hiring and saying, “Oh, I have too much business as a professional policy abuser and I need more skilled workers.” People are looking for jobs. “I’m really great on this and that, is there anyone that can hire me?” It’s a job marketplace. It’s probably been there for decades also since e-commerce started. But the level of sophistication and the scale are vertical leaning, we’re seeing this growing in an alarming pace and becoming more and more sophisticated.

Yvette Bohanan:

So anytime we see professionalization and by professionalization I’m referring to the supply chain, the hiring and recruiting of people into the scheme, all of that, that makes it look like if this were a legitimate business, you’d have all of these functions. This is an illegal business. You have all of these functions. That’s what we refer to as the professionalization of the scheme or the tactics. And here we’re saying they pretty much got it all when it comes to policy abuse now.

Chris Uriarte:

Yeah, we’re seeing the business model essentially mature here, which is following what we’ve seen in other types of fraud. We’ve certainly seen fraud as a service around now for many years, probably for the greater part of a decade as these criminals have gotten more sophisticated. We’ve seen this in the security world as well, where criminals have learned that they don’t have to write their own malware anymore, for example. Their own ransomware is they could purchase ransomware as a service from proven criminals who have had success with certain types of attacks. So it’s no surprise that we’re seeing this on the policy of use side either. And I think it’s a testament to how successful some of these individuals have been to see it mature to this point for sure.

Eyal Elazar:

Yeah. Yeah. And what’s funny, if you look at, for example, resellers and you look at sneaker bots, this is definitely something that, hey, merchant is very clear. This is a limited edition sneaker. You get to buy one. If you’ll be in this physical store, you’ll only get to buy one. And some of these bots are legal. The way to abuse merchants is illegal. It’s illegal to use them maybe, but it’s definitely legal to buy and sell bots. So you would just go on YouTube and you’ll search and you’ll find everything you need to know. It’s not even hidden anymore. So yeah, a lot of people are making a lot of money of this. A lot of money.

Yvette Bohanan:

So what’s the split, do you think, I mean this is kind of an educated guess in a lot of ways, but if you’re looking at the split between these, the individual who goes off the tried and true straight and narrow path versus this professionalized organized policy abuse rings and “dark industry” or something, if you will, where do you see it sort of penciling out? How much is on one side of the equation, how much is on the other?

Eyal Elazar:

Definitely there are more occasional abusers. There are more one-off abusers, definitely by far. But that, I didn’t know if this is the right question. The right question is if you look at the damage and the impact they have on your losses, how would you look at the split? And we actually see that if you can identify the product there is mind blowing. If you can identify less than 0.1% of your customers as someone who performs in systematic abuse, you’ll be able to save millions of dollars, millions a year. The correlation between the more systematic a person is the bigger the damage. And people use a lot of different ways to hide their true identity. And when they work with a specific merchant, they will have each and every time different address, different payment methods, Apple Pay, Google Pay, they will manipulate their address to make it seem like it’s a different one.

Different names, different emails, different devices, different credit card, you name it, different phone numbers. Now, when we use our technology to understand who a customer really is across all accounts, and as we leverage our entire merchant networking, we’re able to connect those dots in an intelligent way using AI. We can see cases where someone will deploy 200, 300 and 400 different accounts in one specific merchant, and each and every account will have at least one INR claim or one promo signup or things like that. The scale here is meaning ridiculous. So it’s not just about how the manipulation gets split, it’s also about where do you want to draw the line and where the person that’s costing the most amount of money.

Yvette Bohanan:

When you pick up a pattern and you know that it’s one person or ring that’s creating hundreds or thousands of accounts, but each account has one return here, one return there, maybe a few don’t have any returns. Yeah, they’re really trying to mess with you. And then you are basically advising a client like, shut this or shut all of these accounts down. They’re all emanating from a bad actor. I’m sure you’re giving them as much information as you can to make the point. Do people resist that though? Do merchants resist that? Is there a pushback here that people just can’t believe that it’s operating at this scale and this magnitude that you’re describing? Because it’s really quite astounding if people don’t see it in the data, if they’re not connecting appeasement to returns, to marketing budgets, to whatever, if they’re not connecting the dots on their side and you’re showing up with this data, what do they say?

Eyal Elazar:

So first of all, after we present them with, and we do a lot of education with our partners, we show them what we see on the dark web. We show them what our engines have detected in their store, and it’s almost impossible not to understand how bad it is, but I think this is also where it gets a little tricky because when you’re dealing with stolen credit cards, you have a very clear question that you’re asking, is this the true call code or not the true account code or not? If it’s not locked in a checkout, it’s a very question at a single point with a very clear yes and no type of response here. It’s not a question of whether or not they want to do something about it because what they want is simple. They want to make sure no one receives an empty box.

They want to make sure that when someone is saying that they never got an item, that they never got an item, they want to trust a customer and they want to know who’s doing that. But when they’re trying to think about how to go about it, this is where it becomes super complicated to them sometimes, because like you mentioned, do you want to act upon it when someone has two, three different accounts or when they have five accounts where they have 10 accounts, do you want to do something when someone is a checkout and say, no, you are a serial abuser? I definitely don’t want you in the store. Or do you want to wait and do something in claim and let them buy? Just don’t give them the refund. And can you do it with returns? They want to return something? Can you tell them “No, you’re not allowed to return it”?

So there’s a lot of different options there. And I think that a lot of merchants, again, when we originally started talking with them, they didn’t really know how to define that thread on when enough is enough. There are so many data points and accounts and how many returns and how many refunds, and this is where the equation became really complicated. And a lot of merchants got stuck in this type of rabbit hole where they’re always trying to redefine what that means to them and how many counts and how many promo and if there is too much what to do with it.

And this is also one of the things that we’re trying to simplify. I think that machine learning has a lot to offer, not just to identify where there’s a bad actor or a bad customer or a bad pattern. It’s also what is the best type of response. And merchants are actively doing stuff to prevent this and they’re very successful. So I haven’t been in a case where someone doesn’t believe the numbers that they’re seeing. It’s whether or not they feel like they can get the organization to back that up and to start actioning on something.

Yvette Bohanan:

So where does this show up when you say getting the organization to back it up, couple of things we might want to talk about on that, because that’s sometimes hard to do. Where do you point on the P&L to say, this is where the problem is showing up in your numbers, in your financials, and what teams are typically most affected by this? Who has to be around the table and in the room and what numbers do they need to look at?

Eyal Elazar:

Yeah, that’s part of the problem everywhere. I mean there’s a financial problem with physical goods. There’s logistics, there’s customer service absolutely there. They have to address the people calling in and they have to be equipped. You can’t have the same person trying to give the best customer experience and trying to understand if someone’s lying at the same time. Definitely payments and fraud managers are involved. Sometimes we see organizations with dedicated functions, a return product manager, a refund product manager. So I think a lot of people need and they have to be involved. But one of the first thing that I think a merchant should a themselves, like do I have a clear owner in my organization to deal with this? Is there a person that is tasked with discovering payment fraud? There’s a clear fraud manager, a persona and a team designed to tackle this problem with policy abuse. Who is that?

And we see that the organizations that don’t have a clear understanding and tasking of who is the decision maker, who has a clear KPI of reducing this impact while also not impacting customer experience, it’s almost impossible for those organizations to really scale up and prevent these losses.

Chris Uriarte:

I think there’s a couple of things here. I think what’s an interesting story here that pointing right to the P&L question and the impact there is as we were doing research for this show, and I was reading scanning the Wall Street Journal and the different earnings reports that came out, we saw an earnings report last week that came from Dick’s Sporting Goods, who’s the largest sporting good retailer here in the US large, very large e-commerce profile as well. And their numbers didn’t hit expectations. In fact, they missed by quite a bit. And the number one thing that they quoted as the cause for them not hitting their numbers was a significant increase in overall shrinkage both in store and online. And I found that to be really, really interesting.

We’ve talked about shrinkage from a retailer perspective since the beginning of time with retailers, but we’re getting to a point now where it’s a headline item when you’re talking to Wall Street analysts about your earning, this is not just a problem related to shoplifting or employee theft in store anymore like we were used to for many decades, this is now a front page headline issue that’s gone omnichannel essentially.

Yvette Bohanan:

Yeah. And what’s interesting is they used to bring in the security people or the police for shoplifters and walk them out of the store with handcuffs on, I’m showing my age here, and there are some states, their laws are sort of, they’re written in a way that certain types of policy abuse, certain types of first party fraud would fall under illegal activity and could be prosecuted. But we haven’t seen a lot of merchants actually, at least not in public, like going after people, right? We’re seeing more in the financial reporting or we’re seeing things, I’ve seen articles where stores are shutting down in some places because there’s just too much shoplifting going on. So the physical locations are shutting down.

Chris Uriarte:

Yeah, it’s a very difficult thing for a merchant to be successful at prosecuting these types of cases. They would have to be very, very, very large and organized in order for law enforcement typically to find interest in something like this. The other thing I think that was very interesting is your point about the organizational aspect of this and merchants having to be prepared really from an organizational role perspective and a skills perspective. So I assume if you look at historical fraud, maybe first party fraud, third party fraud and policy abuse, if you created a Venn diagram, there’s probably a little bit of overlap in different types of techniques or different types of actors, and perhaps there’s some tools that are helpful and common between all of them. But this that we’re talking about here really sounds like you require almost a very different level of expertise and experience to be effective at both detecting and also trying to figure out how you deal with this from a customer perspective, from an organizational policy and rules perspective.

Eyal Elazar:

Absolutely. I mean, first of all, this is costing, for a lot of merchants, this is costing them more than fraud.

Yvette Bohanan:

The traditional third party fraud.

Eyal Elazar:

Yes. Chargebacks.

Yvette Bohanan:

ATO, all that third party where the victim is the account holder.

Eyal Elazar:

Yes. So it’s costing them more. You mentioned shrinkage and how huge a problem that is, even when this is not abusive. Even when this is done, people are just ordering, returning, and I’ve talked about the survey that we have coming up. We actually see that the majority of merchants say, that more than 50% of the merchandise that they supposedly get back is not being restocked at all.

Chris Uriarte:

Wow.

Eyal Elazar:

Either they’re not getting it or not in a good condition, or sometimes it’s just too much. We know of certain merchants that have thousands of refund and return payments a day, thousands a day, how can they even handle that much merchandise? So they have some rules and they just toss things away. And so yes, this is a force to be reckoned with. I think that merchants have to take it very seriously.

There’s always a debate with merchants that maybe this is just another type of fraud and a fraudster is a fraudster. But I tend to think that first of all, we’ve talked about the different spectrum of abuse and people who sign up twice isn’t the same as sending an empty box. And you have to address that spectrum. And also we have to remember with policy, you are dealing not with transactions or orders when you dealing with people, and they are lifetime value when you’re telling someone, “You know what? You cannot shop here anymore. We think you’re an abuser. You know what? You’re not going to get your money back. We believe you actually got your item, or you won’t be able to sign up to our loyalty program.” You are risking that customer. So the level of complexity and the table stakes are definitely different.

Yvette Bohanan:

Very high.

Eyal Elazar:

But still we see that sometimes people are trying, and this is why I’m against the classic fraud is fraud because then they try to use fraud methods to fight off policy abuse. And that’s not very efficient. And this is why we believe specific challenges require specific solutions.

Yvette Bohanan:

So there’s the solution that is required. There’s a mindset that goes with it that’s a little bit different than the traditional third party fraud mindset of what you’re going after and who you’re going after. There’s a big spectrum. A lot of times we hear teams going back to the teams, sort of like different teams associated with this. And a lot of times you also have a compliance group depending on the type of merchant and the activity that they’re doing or whatever. So you have all of these different groups trying to stop different customers. And usually someone in a leadership role is like, how do I know you’re not all just blocking good revenue all the time. Is there a compounding effect here? So is it better to try to have a team focused on this more holistically or is it better to have teams that are specialized in dealing with this stuff? What’s the most effective org structure that you’ve seen? If you had a blank piece of paper, how would you draw this out?

Eyal Elazar:

Unfortunately, I’ll be honest, I haven’t found a magical answer. I think that it’s so very persona related. Who is the person that is tasked? Is this a strong enough person that can handle the organization, that can educate the organization? And that could get the entire array of departments working together. And sometimes I see good payment leaders doing it. Sometimes it’s a good product managers do it. And sometimes I see fantastic fraud managers and loss prevention leaders that are really skilled at doing that as well. But you have to have that person. That person has to be a strong enough person and you have to get management to back them up. And you mentioned something which I always find funny because how do we know we’re not just turning down good customers? And I think this is what we saw with frauds while back, you’re canceling fraudulent orders to avoid hogbacks, and then the CFO would come to you and say, oh, why are you throwing away all these good orders?

And you have to educate them that you’re not turning down revenue, you’re preventing losses. And this type of education should also take place with policy. Today the connection between union policies and growth is very clear. But the connection to losses, sometimes it’s not. You have to understand it and educate everyone around the table to know and give you the right support. Because if you want to tell someone the claim that they’re not getting something they’re not taught, if you want to block someone at checkout because they’re doing something that they shouldn’t, you need to have that ability.

Yvette Bohanan:

So before we wrap up here, we’ve painted a pretty dramatic picture. This is a big issue right now and it’s complicated. It’s complicated at a lot of levels. If you’re a merchant listening right now, you have to ask this on your behalf to both of you. What are the top three to five things a merchant should be doing right now, starting today? They turn off this podcast, they’ve made it this far. We can’t just leave them hanging. What are the three to five actions to say, okay, get started on getting your mind around this and helping your organization. What should you do?

Eyal Elazar:

So first, you made me feel really bad about panicking people to this.

Yvette Bohanan:

I didn’t mean to do that.

Eyal Elazar:

I just want to start and say to whoever’s listening that you are not alone in this. And I think there is comfort in that This is someone everyone are dealing with. This is a phenomenon. This is big. First of all, you are not alone. Take that into consideration and don’t panic. I think that if I were to craft a couple of tips first, again, this is a new journey. While this is not new, the scale of this problem is, and this is going at like 75% year over year. This is massive. And educate yourself, find places and educate your organization. You all have to understand the scale of the problem. You all have to understand where it’s meaning. You all have to understand exactly what you want to do and what to happen in your store. And the more you know about the problem, the better you are in solving it. So this is the first thing.

Then definitely get alignment across the organization. You have so many different people in it. Define the actual decision maker and the person tasked with sorting it out. Have the right KPIs to that person. It’s not just reducing losses, it’s also maybe avoiding false declines. Make sure you’re clear on what your expectations are and have again, everyone around the table, you mentioned legal and terms and conditions, understand what your policies were and make sure your terms and conditions, first of all, reflect what you agree and don’t agree to happen in your store. Third is probably prioritize. And this is something we see very often. We see people saying, “Oh, I have this type of problem, that type of problem, that type of problem. This promo and this geo.” There is no, and I’m sorry for being to have more bad news. There is no magic button than you can press. And tomorrow your problems will be solved. There’s a lot of great ways to get you halfway and more.

There is great, there’s steps that you can definitely take, but you cannot take on too much in one go. Your organization has to slowly adjust. So let’s say tomorrow morning you flip a switch and you know exactly what claims abuse and what order and who’s bad, who’s not. It doesn’t mean you have the organization behind you ready to action. So make sure, again, brace yourself. This is a journey. Start by prioritizing, understand what your biggest challenge is, solve that. Then make sure you find it a scalable way to start hacking away the problem, challenge by challenge. Four is you’re not alone so collaborate. Talk to your peers. You wouldn’t believe how these abusers act. They’re like a hive, they share best practices and tips and everything. As soon as someone knows how to abuse you, everyone in this hive will know. So you need to be the same.

You can’t go at it alone. Talk to your peers, talk to your colleagues and collaborate with your partners and make sure that you find the right type of people to educate you and to help you solve this problem. It’s so important when we solve it for our merchants, to use our merchant network data to understand what’s happening elsewhere. If someone’s an abuser in one place, you want to know about it even before they step through a new store. AI and machine learning goes such a long because people are extremely sophisticated. This isn’t a person with a cheat sheet trying to do a certain I know, just change one note and just try it again. No, these are people who know what they do. You need to have a serious solution that puts you two steps ahead and not one step back because this is evolving all the time.

And last thing I would say, I have to talk about the silver lining. I think that while this is a huge challenge, this forces us all to look at our customers with a fresh set of eyes, understand which customers are trustworthy, profitable, which are not. And I think this is also some type of opportunity. And once you understand who to trust and you know who you want to stop and who’s the really bad players, you also know who the really good ones are.

So you mentioned when you want to tell someone, you know what, keep this item. You know what, here you’ve got 20% off. These are another 20% off. When you know someone who’s really good, this is a chance to give them even better service. When we stop this one size fit all policy and start to provide this type of privileges based on how good of a customer you are, this eventually will become a method for you to offer more to your customers in a scalable way, which I think is something that we should all look for and not just focus on stopping the bad. Now we have to look at it at both sites. How do we stop the bad? How do we give more to the good? So yeah, I always like to end things with a positive point.

Yvette Bohanan:

I like that. I like that. So Chris, Eyal, thank you very much. This has been a very interesting conversation and I really appreciate it and Eyal, I really appreciate it that you’re sharing some of these insights. I know the customer survey is out on your website right at Riskified, and you’ll have a merchant survey available out there too, if folks listening want to download the survey and see more of these results that are quite compelling.

Eyal Elazar:

Yes. The new report is coming out in two weeks. I think it’s very insightful, and again, it’s just part of new education.

Yvette Bohanan:

It should help. That’s awesome. So thank you very much. We’ll have to bring you back with your mom one of these days. I’m looking forward to this.

To all of you listening, thanks for joining us and until next time, keep up the good work. Take all this new information to heart. No matter what part of your organization you’re in, listen to each other with empathy and share your tips, share your observations, and become stronger. Okay, and until next time, bye for now.

If you enjoy Payments on Fire, someone else might too. So please feel free to share this podcast on your favorite social media outlet. Payments on Fire is a production of Glenbrook Partners. Glenbrook is a leading global consulting and education firm to the payments industry. Learn more and connect with us by visiting our website at glenbrook.com. All opinions expressed on our podcast are those of our hosts and guests. While companies featured or mentioned on our show may be clients of Glenbrook, Glenbrook receives no compensation for podcasts. No mention of any company or specific offering should be construed as an endorsement of that company’s products or services.